This is an archived site. This site is no longer being maintained or reviewed for broken links.

Down to the Sea for Science – Science Feature

The Atlantic’s Mighty Meandering River: A Short History of WHOI Gulf Stream Research

| Download PDF for more complete text and additional figures and photos » |

|

|

An electronic current meter goes over the side of Crawford in 1965. Development of modern, long-lived current meters was vital to progress in Gulf Stream research. (WHOI Archives Photo) |

|

|

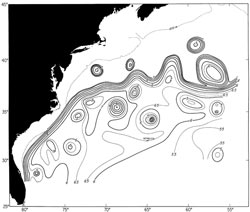

This chart of 1975 hydrographic and satellite data shows the path of the Gulf Stream and a number of warm-core and cold-core rings (north and south of the stream, respectively) that have spun off it. This was the first attempt to create a “weather map” for the northwestern Atlantic Ocean. The flow is charted using the depth (in hundreds of meters) of a water layer registering 59°F (15°C), which years of research have shown to be a reliable indicator of the surface current. (Figure courtesy of Phil Richardson) |

The Gulf Stream is the major current system closest to WHOI, and it has been an important subject of study throughout the Institution’s history. Columbus Iselin described the circulation of the western North Atlantic in a 1936 paper based on extensive but widely spaced temperature and salinity measurements from Atlantis, using an array of reversing thermometers and sample bottles. Over time, more capable ships, better instrumentation, and the determination of those willing to spend long, hard days at sea produced an ever-clearer picture of the stream itself, related features, and its place in global circulation.

World War II brought two significant advances to this work—more accurate navigation in the form of loran (based on radio signals sent out by shore-based stations) and the bathythermograph (BT). In the postwar period, scientists could detect the finer structure of the stream, its twists and turns, narrowness and intensity, and eddies and meanders.

During the three-week, six-ship Operation Cabot survey in 1950, physical oceanographers both collected extensive data and, for the first time, followed the evolution of a cold core eddy as it moved southward and pinched off from the Gulf Stream. The following four decades would bring intense scrutiny of both cold core (south of the stream) and warm core (north of the stream) eddies or “rings,” revealing that ring behavior includes splitting into pieces, merging with one another, interacting with the Gulf Stream, reforming as modified rings, and coalescing completely with the stream.

In the 1950s, a combination of new theories, neutrally buoyant floats ballasted to follow deep-water motions, extension of hydrocasts to the deep sea, and rotating tank experiments revealed the Gulf Stream’s expression down to the very bottom of the water column as well as the deep western countercurrent that flows south sometimes below and sometimes near the stream.

The next instrumentation step needed was a means to make long-term measurements, a very challenging task due to the variability of the swiftly flowing currents. Experimentation with moorings and current meters began in the late 1950s, and it took ten to fifteen years of unremitting effort for the WHOI Buoy Group to develop a trustworthy system for routine use. The moored current meters brought reliable estimates of mean current flow in the vicinity of and under the Gulf Stream and revealed fluctuations with time and variations in speed of flow.

Radio- and later satellite-tracked surface drifters brought new definition to the stream’s upper flows in the l960s and 1970s. During the same period, early subsurface floats that required a following ship to chart their progress gave way to long-lived sofar floats tracked through moored listening stations. Both provided the means for more detailed understanding of Gulf Stream fluctuations, meanders, and rings.

The late twentieth century brought continued refinement of techniques and synthesis of Gulf Stream data. Today, WHOI scientists and their colleagues apply their long experience with investigations of the western North Atlantic to circulation studies worldwide. They employ expendable BTs, conductivity-temperature-depth profilers, satellite navigation, and acoustic Doppler current profilers—the modern versions of the BT, hydrostation, loran, and early current meters—as well as advanced profiling floats and other state-of-the-art tools such as satellite altimetry and infrared imaging.

This feature is based on an unpublished 2004 manuscript by WHOI scientist emeritus Philip L. Richardson, entitled “WHOI and the Gulf Stream.”