This is an archived site. This site is no longer being maintained or reviewed for broken links.

Down to the Sea for Science – Science Feature

Fragile—but Robust—Denizens of the Deep: A Short History of WHOI Research on “Jellies”

|

|

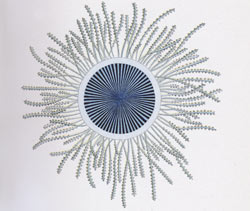

As scientists reveal more about the lives of jellies, these creatures become ever more fascinating in their beautiful diversity of form and function. This deep-sea comb jelly, Bathocyroe fosteri, is named for Alvin pilot Dudley Foster, who collected the first specimens. It is about two inches tall and lives in all oceans at depths below 1,000 feet (300 meters). (Photo by Larry Madin) |

|

|

Open-ocean scuba diving from research vessels began to reveal more about the world of jellies during the cruise in the 1970s. To make their collections and observations and avoid becoming lost in the vast ocean, the divers use a tether system, with one person serving as “safety” at its apex. Underwater lights enable them to make night dives to view and collect jellies when many species are more active and appear in greater numbers. (Photo by Larry Madin) |

Because their bodies have no hard parts, gelatinous animals, commonly called “jellies,” have always been fascinating and elusive to naturalists. They were already a favorite subject for Henry Bigelow when he was the curator of the medusae on Alexander Agassiz’s 1901 Maldive Island voyage. His drawings of Porpita lutkeana, at the bottom of this page, and Timoides agassizii, on page 6, are still accurate and beautiful today. During WHOI’s early years, Bigelow and his associate Mary Sears continued their research on jellyfish and their relatives.

Decades later, gelatinous animals returned to the list of WHOI research interests when Richard Harbison and Larry Madin joined the Biology Department in the 1970s. Harbison was a biochemist by training but soon became interested in the biology of salps, a type of swimming sea squirt. Madin was finishing his Ph.D. at the University of California, Davis, under William Hamner, who had pioneered new in situ techniques for studying fragile, gelatinous, planktonlike salps in their natural environment. Joining WHOI as a postdoctoral scholar, Madin teamed up with Harbison to introduce “blue-water diving” to WHOI vessels. This approach—scuba diving in open-ocean water to observe and collect delicate jellies that seldom survive net collection—opened up many new lines of research on life history, behavior, energetics, and distribution.

Within a few years the depth limits of scuba diving were overcome by using Alvin to extend observation and sampling into much deeper water. Submersible dives to “midwater” depths (near 1,000 meters, or 3,300 feet) in the late 1970s revealed abundant and diverse jellies, including many unknown species that had never been collected with conventional nets. Subsequent midwater dives by Madin, Harbison, and colleagues elsewhere have yielded a hundred or more species new to science but common in the mid-depths of the ocean.

This work has opened a new window on life in the waters of the open sea, revealing and documenting the role of gelatinous animals as integral parts of plankton communities, instead of mere curiosities or nuisances. Henry Bigelow would no doubt be pleased that today’s WHOI biologists continue to expand our knowledge of gelatinous animals, documenting their history, role, and effects on large marine systems and processes.

This feature was contributed by WHOI senior scientist Laurence P. Madin, who is also director of the Ocean Life Institute, and science writer Katherine Madin.

|

|

|

Henry Bigewlow drew this medusa, Porpita lutkeana, during his 1901 trip to the Maldive Islands. (Drawing by Henry Bigelow, courtesy of MBL Archives) |