This is an archived site. This site is no longer being maintained or reviewed for broken links.

Down to the Sea for Science – Science Feature

Pioneering Chemical Oceanography: A Short History of WHOI Research in Marine Chemistry

|

|

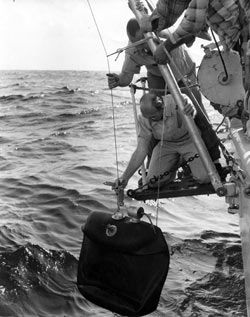

Vaughan Bowen, kneeling, worked with WHOI shop personnel beginning in the 1950s to develop large-volume water samplers for his work on fission products in seawater. Here, a first-generation sampler goes down under vacuum. (WHOI Archives Photo) |

|

|

Max Blumer, who joined the WHOI staff in 1960, was a pioneer in detecting trace amounts of organic compounds in seawater and sediment. (Photo by Bill Lambert) |

Norris Rakestraw, an assistant professor of chemistry at Brown University, was among the earliest WHOI scientific-staff members. He and his colleagues kept the Institution in the mainstream of pioneering chemical oceanography during its first decade. Their work included examining the seasonal variations of various substances in seawater at stations in the Gulf of Maine and on a line from Woods Hole to Bermuda. Studies of marine biological chemistry initiated by Alfred Redfield continued for many years and eventually yielded the Redfield/Ketchum/Richards ratios of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus in phytoplankton, particulate matter, and dissolved forms. These ratios are still applied today in studies of oceanic biogeochemistry.

During World War II and in the immediate postwar years, the chemical component of WHOI research focused largely on antifouling paints for ships and the chemistry of explosives. With staff relocations, there was a fallow period for marine chemistry in the late 1940s, but it did not last long. Soon there was new work on oxygen minimum zones and their relationships to underlying sediments, as well as research interest that would last for decades on the inputs, fates, and effects of the oceanic disposal of various types of wastes.

Studies of fission products in seawater in the mid-1950s by Vaughan Bowen indicated that some isotopes were removed rapidly from upper layers of the sea and initiated longstanding work on the transport of a variety of substances through the water column aboard descending particles. Bowen’s laboratory became a world leader in investigations of fission-product radionuclides in the oceans.

Max Blumer joined the staff in 1960 to begin an ambitious program of extracting and isolating trace amounts of organic compounds from seawater and sediments that led to the Institution’s prominence in marine organic geochemistry.

Henry Bigelow’s view of oceanography as an integrated science was evident in the initial organization of science departments: chemistry was initially paired with biology in 1962 and then with geology the following year when petroleum chemist John Hunt became the first permanent department chair for these disciplines. A reorganization later in the 1960s created both a chemistry and a geology and geophysics department.

Focusing on major and minor elements in seawater, relationships between dissolved and particulate matter, and sediment and underwater-basalt geochemistry, the department was on its way to becoming one of the foremost chemical oceanography and marine geochemistry research efforts in the world. A technical staff that provides outstanding analytical expertise has been key to maintaining that leadership.

With growing interest in pollution, WHOI staff made some of the earliest open-ocean measurements of DDT and initiated an abiding interest in the persistence of oil spilled or otherwise transmitted to the marine environment.

Research in today’s Department of Marine Chemistry and Geochemistry encompasses all of the areas mentioned above and also includes, among other subjects, studies of exchanges at the air-sea interface, the ocean carbon cycle, microbial and planktonic processes, hydrothermal systems, paleoceanography, and shoreline groundwater.

This feature is based on an unpublished 2004 manuscript entitled “Chemical Oceanography/ Marine Chemistry and Geochemistry at WHOI” written by John W. Farrington, WHOI senior scientist and vice president for academic programs and dean.