This is an archived site. This site is no longer being maintained or reviewed for broken links.

Employee Portrait Gallery—Cliff Winget

|

|

|

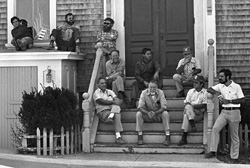

Pleasant weather in Woods Hole village draws people to Community Hall’s steps on Water Street in Woods Hole village. Cliff Winget is front and center in this 1980 photo. Others in the picture, from left, are, top row: Woody Woodward, Charlie Peters, and Steve Page; middle row, Whitey White, John Romiza, and Bobby Weeks; bottom row, Ed Phares (to Cliff’s left), Ed Denton, and Mo Moniz. Historic footnote: One sunny day in 1981, a group of women held a sit-in to “protest” male dominance of the steps. Carl Young was visiting the ladies. (Photo by Shelley Dawicki)

|

The Novocain was beginning to take effect when Cliff Winget first heard about Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. “You’d fit in great with the Alvin group,” his New Jersey dentist said. “They’re a bunch of wild and woolly misfits. You’d like ’em. I’ll connect you with my friend Ronny Veeder.”

Cuttyhunk native Veeder, manager of the WHOI development program, was Cliff’s ticket off a wandering path that took him from the Army Air Corps (where he studied engineering, was a test pilot, and did a stint on the DEW [Distant Early Warning] line in Greenland) to the Walter Kidde company (where he designed rocket engines for Lockheed) and Boeing (where he worked on aircraft electrical and hydraulic systems). Cliff joined the Alvin Group in 1967 during the lean years when the sub’s future was touch and go and the group’s culture was “part engineer, part scientist, and mostly pirate,” he said.

“Cliff’s scope of work was incredible,” said long-time Alvin pilot Dudley Foster. “There is probably not a single system on Alvin where Cliff, at one point or other, wasn’t involved in improving, improvising, or fixing.” The sub’s trim system, for example, used a hydraulic pump from a Beechcraft landing gear. “He had this aviation slant,” Dudley said, “that gave him a creative pull from an area where most ocean engineers have never been.” His Alvin innovations conservatively number around 100.

Cliff describes his proudest moment as the Alvin overhaul following the sub’s recovery after nearly a year in 5,000 feet of water due to an accidental sinking in 1968. “Nobody knew what we would find, or how much damage there would be,” Cliff recalled. “The Navy wanted to just forget about it. I said we could rebuild it for $750,000. I just pulled that number out of the air, and it turned out to be correct.”

In his last ten years at WHOI (he retired in 1985), Cliff contributed to diverse projects. For Fred Grassle, now at Rutgers University, he designed a multichamber basket to collect and isolate microbial samples near hydrothermal vents. “It was really a very clever device, with a complex array of pumps and sample chambers,” Grassle said. “But the most clever part of all was its ease of use from a single console inside Alvin. Almost any engineer could make a device that’s hard to use—Cliff made it easy.”

Working with WHOI’s Charley Hollister and colleagues, Cliff created an engineering marvel called SeaDuct, a massive assembly of pipes, motors, and valves, designed to measure sediment movement in situ. When assembled, SeaDuct was so huge, the doors at the Coastal Research Lab where it was built had to be removed to get it out of the building, and only R/V Knorr was large enough to handle it.

“My dad was a banker, and he wanted me to be a banker,” Cliff said. “But I needed to work on something big—something I can hear, see, and smell. I have no regrets—I had tremendous freedom to do what I thought was right, and I would do it all over again—and probably make a whole set of new mistakes!”

[back]